The Velvet Underground: The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967)

It's been awhile, figured I'd cheat a bit and share another excerpt from my book, Jittery White Guy Music:

***

Frankly, I was a little frightened of this album. The reviews I had read left me with the impression that the record was noisy, confrontational, and downright perverted.

I was taking a filmmaking class at the time, a high school elective where we got to make Super 8 movies, with the teacher selecting a few of his favorites for a showing during the school’s biennial arts festival. I made a 5-minute stop-motion animation opus, Jell-O from Outer Space, cubes of red and green Jell-O conquering a miniature town I’d borrowed from my father’s model railroad layout, soundtracked with Pink Floyd’s creepy “Careful with That Axe, Eugene.” (It snagged an honorable mention at the film festival.)

Not surprisingly, the filmmaking class attracted an odd mix from the peripheries of the student body, from the pretentious drama kids to the jocks seeking an easy credit. (Me, I was looking for a breather from my more academically grueling classes, and I had a genuine interest in animation.) There was this one guy in class who regularly wandered in late (when he showed up at all), clad entirely in black at a time when bright pastels were emerging as MTV-driven fashion must-haves, his long, corkscrew-curled hair barely concealing a pair of Walkman headphones that he didn’t bother removing for class.

One day I got up the nerve to ask him what he was listening to.

“The Velvet Underground & Nico. You need to check it out.” It sounded like a dare.

I knew very little about the Velvet Underground or their music. Sure, I knew that they were Lou Reed’s old band, and Lou Reed was the guy who sang “Walk on the Wild Side,” the FM-radio staple that managed to draw airplay notwithstanding its transgressive (in the literal sense) tales of New York drag queens and oral sex and girls singing doo-da-doo (and, really, in 1972, how the hell did Reed get away with all that?). Maybe I’d heard “Sweet Jane” or “Rock & Roll,” but understood these late-period bids at commercial acceptability to be highly unrepresentative of their earlier, far less approachable work.

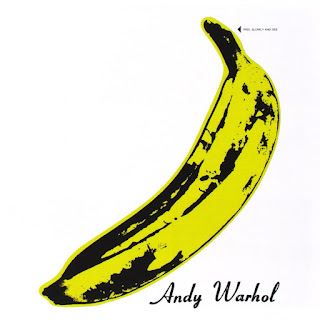

The album cover itself revealed little. Andy Warhol’s iconic banana painting on a plain white background was non-descript to a fault, certainly providing no hint of the menace I’d been assured lay within. The back was slightly more telling, the band hidden behind dark shades, a psychedelic light show flashing across their faces, though still nary a hint of the deviance the record supposedly harbored.

I braced myself for the anticipated sonic assault, the dark tales of heroin and S&M.

Instead, the album opens with the quietly beautiful “Sunday Morning,” a sunshiny ballad; hell, the song sounded like it was played on a freakin’ xylophone. My initial thought was that I’d been had, like the whole Velvets mystique was a practical joke—scare off the masses with threats of noise and degradation, then treat the courageous few to something light and fluffy.

But then the album reversed course, sounding more like I’d expected, setting loose the churning, insistent guitar riff of “Waiting for the Man” as Reed journeys uptown into Harlem to score a fix. And sure, the sound was rough, the subject matter a lot darker than the flowery psychedelia of the band’s 1967 peers, but it was also a pretty great song, a catchy hook buried beneath the squalor.

Much of the remaining album bounced back and forth like that. You’d get pretty ballads and pop tunes (a few sung in a haunting chilly contralto by German chanteuse Nico, who was foisted on the band by Warhol and disappeared after that first album), interspersed among the noisy, kinky, drug-laden bacchanals. But I found both facets of the record equally spellbinding, the alternating embrace of the menacing and serene making it unlike anything I had heard before.

It did quickly become evident, however, that this was not an album I’d be cranking on the family stereo. If my parents had been put off by McCartney’s “Monkberry Moon Delight” and the bubblegum debauchery of that Sweet album, I certainly did not want to see how they’d react to an all-out sonic assault as Lou Reed graphically and unapologetically described inserting the needle into his veins and tasting the whip of the leather-clad dominatrix. This one was strictly headphones-only.

I won’t drag out the tired clichés about how influential the album is, how it changed my life, how it made me want to run out and start a band. The universe’s capacity for exuberant odes to the Velvets’ significance is well past the saturation point. But I will say this: I got through the VU & Nico album feeling liked I had survived the initiation. There was a locked door behind which they kept all the cool music, and I’d just been given a key. Not that I necessarily wanted to hang out with the other members of this exclusive club. That scary guy in the black turtleneck sitting in the back of my filmmaking class never checked in to see if I’d taken his advice, and if I’d approached him one day and told him I was totally swept up by “All Tomorrow’s Parties,” I highly doubt he’d have invited me over after school to chill out with some fruit roll-ups and a little MTV. But a bond had been established, even if he didn’t know it.

That Velvets album also served as my introduction to rock snobbery; it was hard not to feel a little superior when your friends are extolling “Jesse’s Girl” and “Bette Davis Eyes,” and you’d just spent the afternoon listening to “Heroin.” Of course, once I got to college and joined the radio station, I realized I was still way out of my depth. Oh, you’ve heard the first VU album? White Light/White Heat is much more groundbreaking. And where do you stand on the Stooges? The Modern Lovers? Patti Smith? Wire? Still, I at least had some baseline bona fides; I’d crashed the Velvet Underground barrier.

Comments

Post a Comment